Feeding Networks: How Food Moves Through Our Communities

It’s no secret that hunger is a growing challenge in Florida communities. From local leaders to community organizations, many feel called to step up—but where do they begin? We sat down with Patti DeLaCruz, Director of Agency Relations at Second Harvest Food Bank of Central Florida, to talk about how food pantries get started, how they become part of a larger network, and the unique role school-based pantries are playing across the state.

Where do most food pantries come from?

Many families depend on them, but it’s hard to know how they started. Patti explained the answer is more layered than we would think. Often food pantries grow out of small, one-time events organized by faith-based groups—like a Thanksgiving turkey drive or a Christmas Eve meal service. These events, while meant to be temporary, often reveal a deeper, ongoing need in the community. What starts as a single act of generosity can evolve into a permanent mission. When groups decide to formalize their efforts and approach a food bank about becoming a partner, Patti shared that, “We do a lot of re-education about what running a pantry really involves.”

Becoming Part of the Food Banks Network

The process at Second Harvest Food Bank of Central Florida, like many of our food banks, begins with an open enrollment period when organizations can submit an interest form. To qualify, groups must first be a 501(c)(3) nonprofit. The list of other requirements includes transportation capabilities, refrigeration capacity, and record keeping abilities. While every food bank is slightly different, this list from Feeding Tampa Bay lays out in detail their requirements for a partner food pantry.

From there, applications are reviewed, scored based on need, and followed by a site visit. Once approved, orientation and training begin. New partners are introduced to “segments”—groups of pantries with similar systems or locations—so they can problem-solve and share ideas. Coordinators and mentors also provide guidance throughout onboarding. Second Harvest of Central Florida alone partners with more than 700 pantries across seven counties, and one of the core requirements is that pantries must be open year-round—not just during the holidays.

During orientation, new partners learn how to order food online. One key tool is the Power Purchase Program, which lets pantries buy wholesale food directly from manufacturers. They can also access food through the Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP), though this requires additional training and reporting.

A major part of onboarding also includes food safety. The food bank’s agency relations team leads a comprehensive Food Safety Training program that focuses on the primary contact person from each partner agency. That individual is then equipped to train their volunteer pantry staff, ensuring safe handling practices across every site. Food safety standards are intentionally set high—because every neighbor deserves not just access to food, but the dignity of food that is healthy, safe, and handled with care. By providing these essential tools and knowledge, Feeding Florida food banks help pantries maintain high standards while safely distributing food to the communities they serve.

Another option at Second Harvest is The Mart, where pantry representatives can shop during their appointment time while their online food orders are loaded into their vehicles. All food is provided at a shared maintenance fee of $0.19 per pound, which helps offset the food bank’s sourcing and storage costs—especially important for high-demand items like meat. Across Feeding Florida’s network, not all food banks charge a maintenance fee, and for those that do, the cost can range from ten cents to $0.19 per pound.

As for selecting specific food items, Patti explained that most offerings depend on availability, but food banks work hard to listen to their communities and their partner food banks’ needs. If certain foods are requested often, or if they’re culturally significant, food banks try to make them accessible. Beyond food, pantries also receive essentials through the Grocery Alliance, including soap, diapers, toilet paper, and even pet food. These donations help pantries meet the full spectrum of needs in their neighborhoods.

Every pantry in the Feeding Florida Network, and thus the Feeding America Network, must follow two non-negotiable rules:

- Food must be distributed equitably—to everyone, regardless of race, gender, age, religion, sexual orientation, political beliefs, or socioeconomic status.

- Food cannot be sold. Pantries are strictly prohibited from reselling items or charging for food in any way.

Contracts are renewed yearly, with all partners signing a memorandum of agreement. Additional training is available for pantries that struggle to meet requirements. While it’s rare for pantries to be shut down, accountability ensures fairness and trust across the network.

Meeting the Need for Children

School pantries function a bit differently. They may operate as a full pantry or as a smaller produce distribution, often twice a month. Elementary schools typically rely on staff or volunteers to run them, while middle and high schools often let students take the lead.

Older students may oversee ordering, manage inventory, and even design logos and mascots. Sometimes pantry operations are integrated directly into the curriculum, giving students real-world leadership and business skills.

County School Boards must approve any new pantry, and schools are required to meet food safety standards like temperature control and sanitation. While pantries often target schools with high free- or reduced-lunch populations, that’s not a strict requirement. For most school pantries, food is available to students, their families, and staff, but not to the general public.

One standout example Patti highlighted is the University of Central Florida pantry, which provides food and also equips students with valuable business and leadership experience—helping neighbors move beyond the need for emergency food assistance.

Connecting Pantries to Food Banks

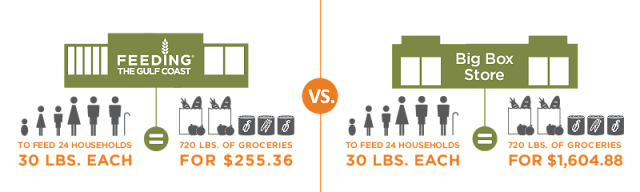

When pantries join the food bank network, they see strength in numbers. By working together, food banks and pantries can negotiate food prices on a nationwide scale, share financial and logistical resources, and provide emotional support to food pantry organizers—many of whom are older adults managing demanding programs. (This graphic from Feeding the Gulf Coast shows what a difference this can make.)

“This should not be another hard job,” said Patti. “We want to walk alongside people with passion and dedication, and give them all the tools they need to do their good work.”

The value of a network becomes even more clear during crises like hurricanes or economic shifts. Collaboration allows communities to respond faster and more effectively than any one group could on its own, with the food pantries becoming critical points of distribution deep within communities.

Building Communities, Feeding Neighbors

Starting a food pantry is not as simple as handing out food, it’s about building community, sustainability, and partnership. With the support of a statewide network, local leaders don’t have to do it alone.

Hunger is a challenge too big for any one person or organization to solve alone, but together, we can make a lasting difference. Whether you feel called to start a pantry, volunteer your time, or simply connect with your local food bank to learn more, there’s a place for you in this work. By getting involved, you help strengthen the network that ensures families across Florida have access to safe, nutritious food year-round. Learn how to partner, volunteer, or support your community pantry through Feeding Florida and your local food bank. Together, we can build healthier, stronger communities—one neighbor at a time.